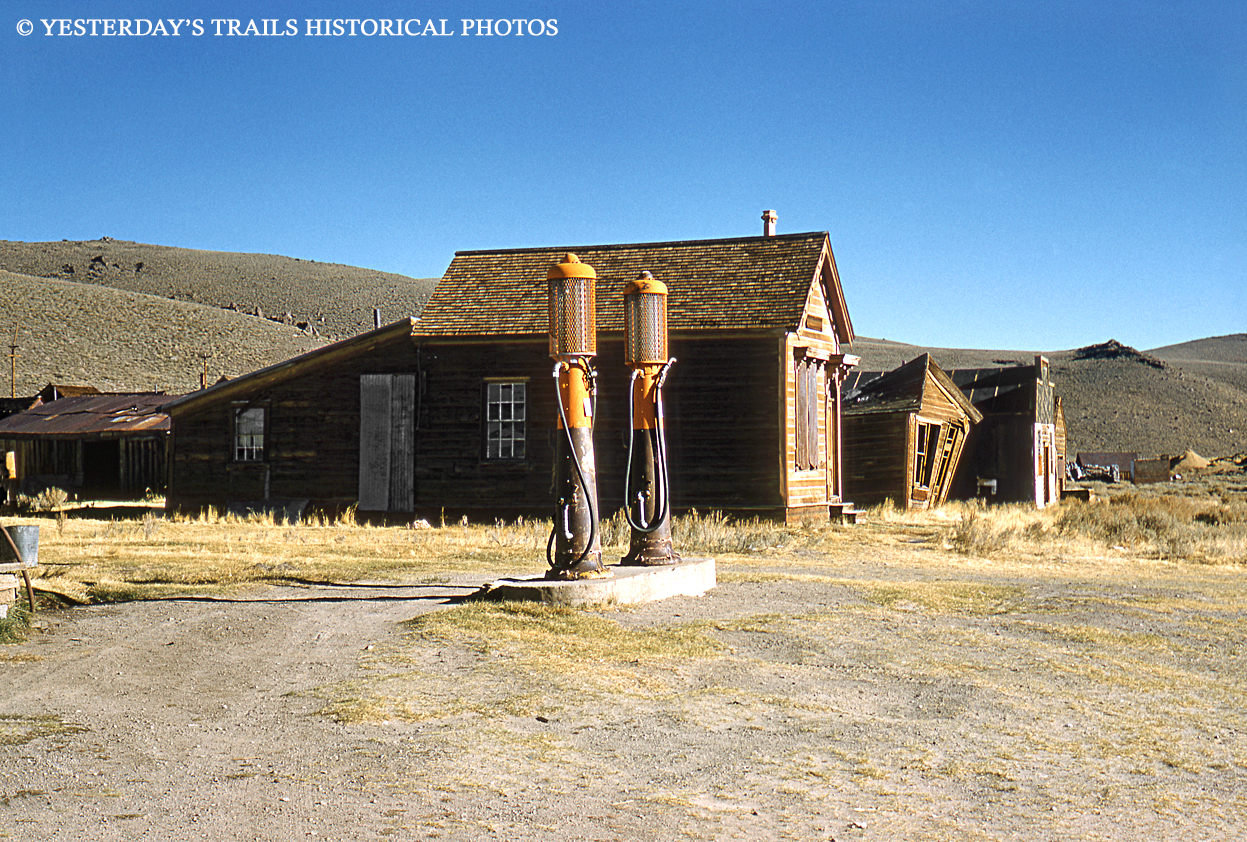

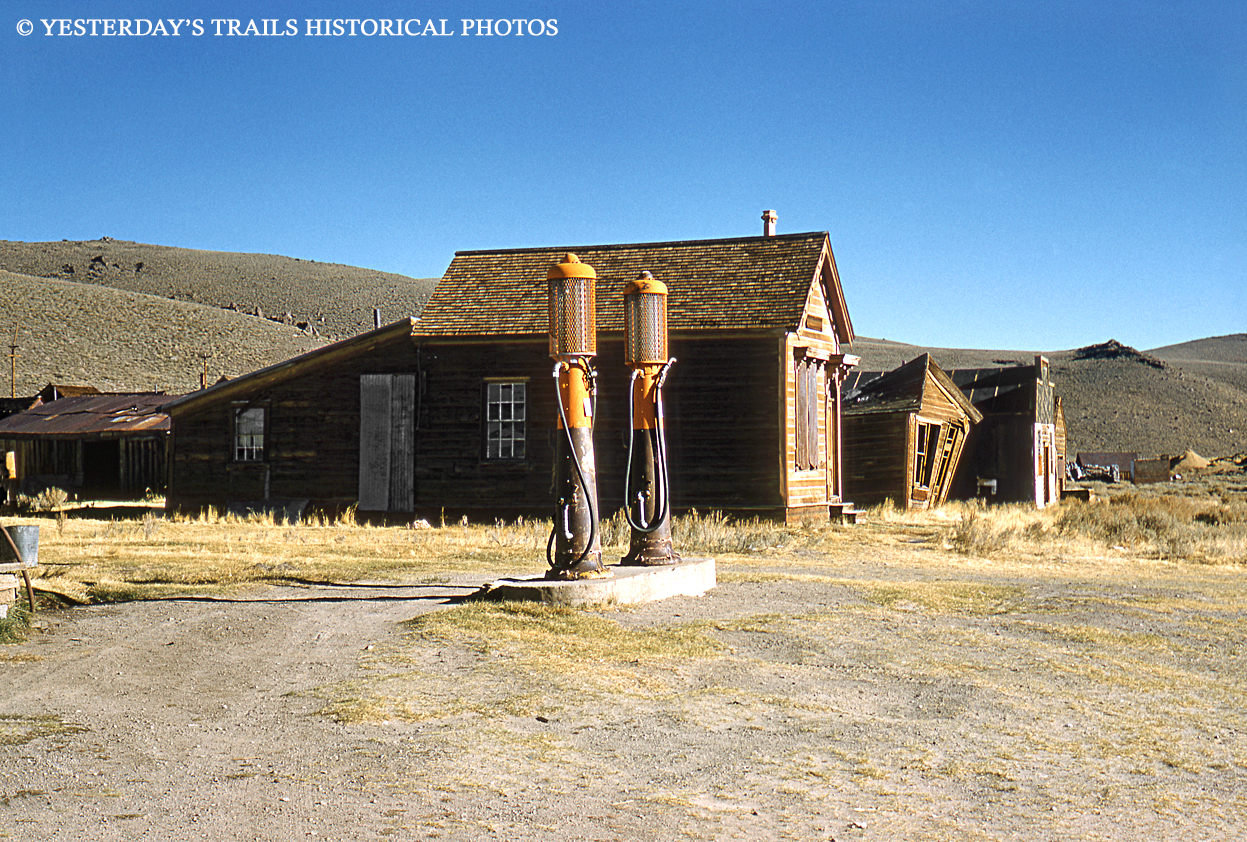

Before the Restoration:

This restoration shows the twin Shell gas pumps along Main street in the ghost town of Bodie, CA as seen in Oct. 1959.

The building behind the pumps was the residence of Eli & Lottie Johl. Eli and a partner, Charles Donnelly, setup the Union Market Butcher Shop. Lottie began her time in Bodie as a prostitute, and eventually married Eli. But, because of her recent past working in the red light district, many people shunned them both.

On September 4, 1932 the U.S. Post Office was moved to the Lottie Johl house, with Mary McDonnell as postmistress.

The building to the right of the Johl house was a carpenter shop. That building has since collapsed & there is no trace of it anymore.

The buildings to the right of that were the Sam Leon Bar (later Hise Restaurant in the 1930’s) and the barber shop next to that.

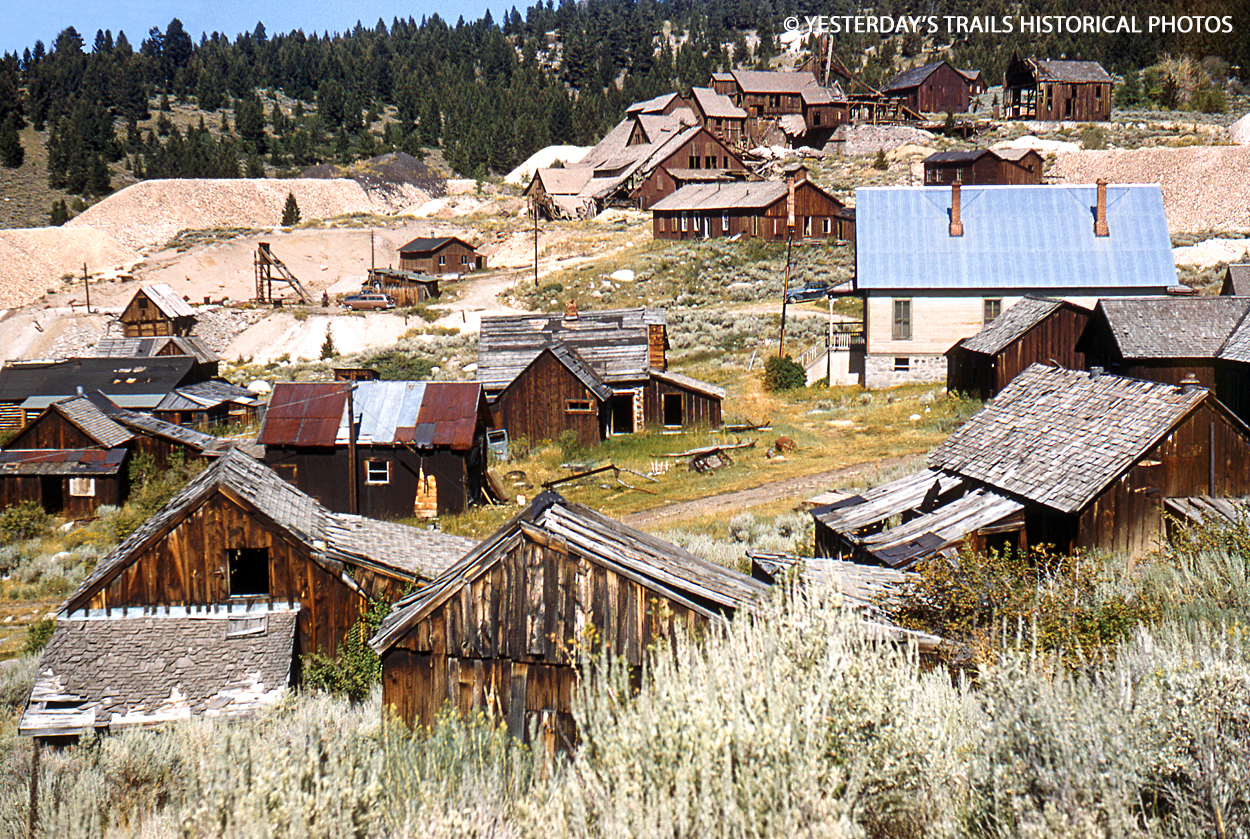

Bodie came into being when a small group of prospectors discovered gold in the hills above the town in 1859. The prospector the town was named after, Wm. S. Bodey, died in a blizzard the following year never seeing the emergence of the town that would be named for him.

In 1876, the Standard Company discovered a profitable deposit of gold-bearing ore, which transformed Bodie from an isolated mining camp comprising a few prospectors and company employees to a Wild West boomtown. By 1879, Bodie had a population of approximately 5,000–7,000 people and rode it’s boomtown status into the late 1880’s. Gold & Silver bullion from the town’s nine stamp mills was shipped to Carson City, Nevada, by way of Aurora, Wellington and Gardnerville. Most shipments were accompanied by armed guards and after the bullion reached Carson City, it was delivered to the mint there, or sent by rail to the mint in San Francisco.

In it’s heyday, Bodie had the amenities of larger towns, including a Wells Fargo Bank, four volunteer fire companies, a brass band, railroad, miners’ and mechanics’ union, several daily newspapers, and a jail. At its peak, 65 saloons lined Main Street, which was a mile long. Murders, shootouts, barroom brawls, and stagecoach holdups were regular occurrences.

The first signs of decline appeared in 1880 and became obvious toward the end of the year. Promising mining booms in Butte, Montana; Tombstone, Arizona; and Utah lured men away from Bodie. The get-rich-quick, single miners who came to the town in the 1870s moved on to these other booms, and Bodie developed into a family-oriented community.

In 1882 residents built the Methodist Church and the Roman Catholic Church (burned in 1932). Despite the population decline, the mines were flourishing, and in 1881, Bodie’s ore production was recorded at a high of $3.1 million. Also in 1881, a narrow-gauge railroad was built called the Bodie Railway & Lumber Company, bringing lumber, cordwood, and mine timbers to the mining district from Mono Mills south of Mono Lake.

A devastating fire in 1892 destroyed a large section of the town core. Though the mining still continued to prosper, the population had significantly declined further & the town continued to mirror that through the early 19 teens. The towns last newspaper ceased production in 1912, the Standard Consolidated Mill closed in 1913 & in 1917, the railway was abandoned & tracks taken up. Though families still resided in town, & several mills still operated, Bodie was declared a “ghost town” in 1915. Despite this designation & a subsequent fire in town in 1932, Bodie still maintained a post office & mill until 1942 when the last mill closed & the town was essentially deserted.

James Cain, President of Southern Consolidated Mining Co., started purchasing the bank, lots, buildings & most of the available property around town during the early 1900 decline, believing the town would experience a resurgence. The town never saw that resurgence & after the 1932 fire & further decline, Cain began hiring some of the last residents as caretakers to protect and maintain the remaining buildings.

In 1961, the town of Bodie was placed on the National Historic Register and in 1962, the State of California purchased the land & buildings from the Cain family and has maintained it as California’s Smallest State Historical Park and in a state or “arrested decay,” meaning that the existing buildings will be maintained as they were but with no improvements.

Visitors to Bodie can visit the buildings and see how they were left when the last residents left over a half century ago. It is considered the best existing example of a frontier mining town today.

Everything in this photo still exists although the remaining white paint on the buildings is long gone & the gas pumps have lost most of the color seen here.