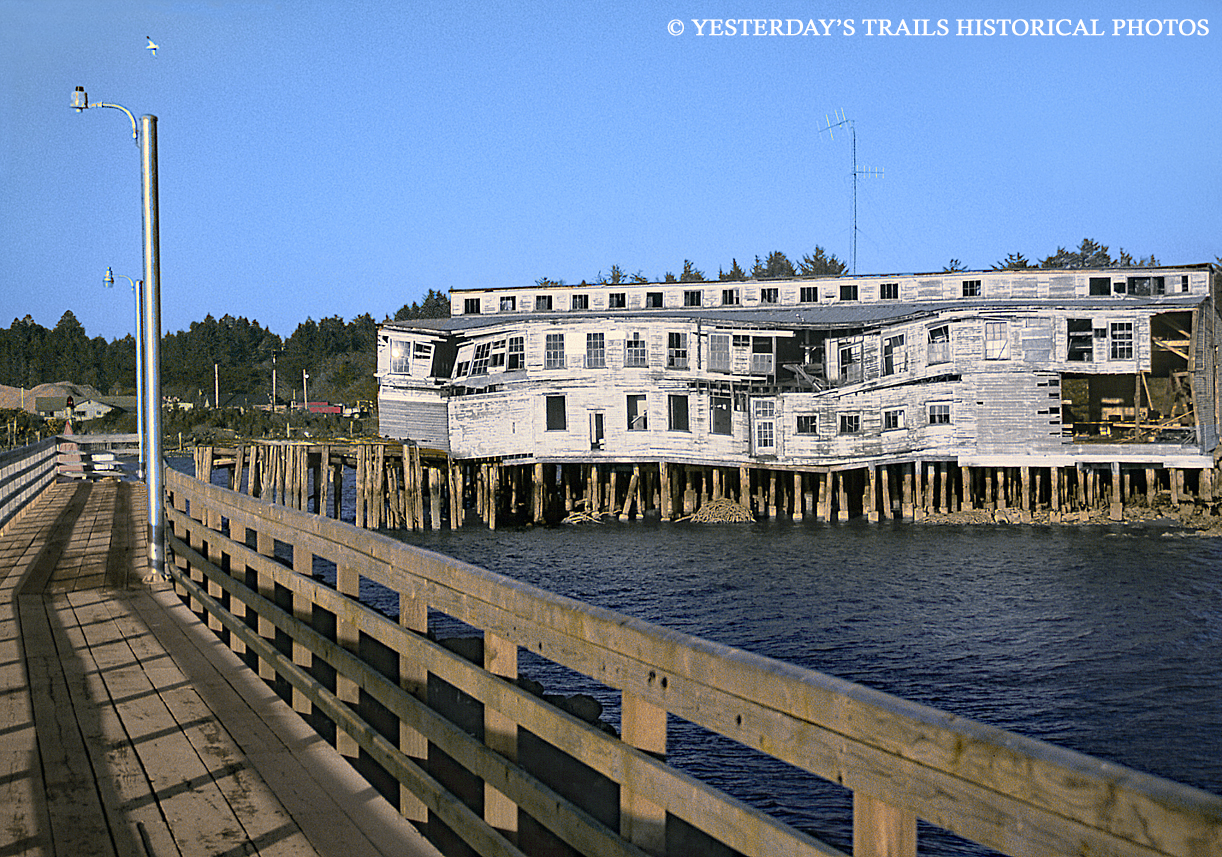

Before the Restoration:

This restoration shows an abandoned residence & car, one of the last buildings that remained standing in the once-thriving company town of Bradwood, Oregon as seen in April 1981.

The town was the company town of the Bradley-Woodward Lumber Company, and was incorporated in July 1930. It’s name was a derivative of the company name. Shortly after the mill began operations, work began on creating the town.

Bradwood was a location on the Columbia River situated between the towns of Knappa & Wauna, Oregon, about 22 miles east of Astoria.

With a shipping port and served by the SP&S railroad, Bradwood became the terminus for the company’s private railroad bringing down logs felled on Nicolai Mountain, milling them at the company mill & shipping finished products out by ship & rail. Lumber from the mill was used to construct the houses & businesses that were built to accommodate the millworkers & their families.

The mill and town thrived during the depression years and throughout World War II but afterward the once abundant timber stands dwindled and the mill ceased operations of it’s privately owned logging railroad. The mill continued on in operations with logs brought in by trucks & purchased log rafts for awhile. At some point, the entire operation was sold to Pope & Talbot Co.

In June 1962 the decision was made to close down the mill and a year later, on June 25th, 1963 the mill & entire town was sold at auction into private hands. Some of the buildings were moved or deconstructed but the rest were simply abandoned.

A major fire in 1965 destroyed the mill & much of the remaining buildings, and another fire in 1984 took care of what buildings remained including the house pictured here.

Today, the property is privately held, no structures or roads remain, and there is no evidence that the little community of Bradwood ever existed. In the mid-2000s, the site was considered for a proposed terminal for receiving liquefied natural gas (LNG). Protests & bankruptcies however derailed that plan and today the site is unimproved with posted “No Trespassing” signs.